NEW YORK (AP) — Daniel Menaker, an award-winning author of fiction and nonfiction and a longtime editor at The New Yorker and Random House who worked with Alice Munro, Salman Rushdie, Colum McCann and many others, has died at age 79.

- ★★★★ Watched by Will Menaker 24 Feb, 2021 8 The greatest aerial tramway-based WW II action movie ever made. Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood go behind enemy lines and deep undercover to break into a castle, high in the Bavarian alps to rescue a general who has the D-Day plan from the clutches of the high command.

- ★★ Watched by Will Menaker 27 Jan, 2021 3 America was a much funner place before we knew that any level of playing football causes CTE, that big fat guys with drinking problems weren't 'cool, fun, party animals' but rather sad, depressed men looking to kill themselves, that guys who brag about giving sophomore girls percs and vicodins to.

Menaker’s son, podcaster Will Menaker, announced on Twitter that he died Monday of pancreatic cancer, with his wife, the writer and editor Katherine Bouton; and his two children at his bed side.

27.2k Followers, 817 Following, 2,006 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Will Menaker (@codydad420). Chapo’s original creators were Matt Christman, Felix Biederman and Will Menaker, three friends who met on Twitter and bonded over a shared far-left political perspective. In early 2016, they were brought together on the podcast Street Fight Radio to criticize and mock the then-recently released film 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi.

“He was me, and I am him in so many ways,” Will Menaker tweeted. “I miss him terribly, but am struck with a profound feeling that I am the luckiest man alive for having been his son.”

Daniel Menaker was the author of several books, including the memoir “My Mistake” and the comic psychological novel “The Treatment,” adapted into a 2007 movie starring Chris Eigeman and Ian Holm. He was also known for the O. Henry Award-winning title story of his collection “The Old Left,” which draws on his early childhood in Greenwich Village and his “red diaper” upbringing: His father allegedly spied on Trotsky in Mexico, where the exiled Russian revolutionary was eventually assassinated, on behalf of the Communist Party; an uncle was named for Friedrich Engels.

In conversation, Menaker was often genial and self-effacing, but he would acknowledge competitive and boastful sides and was haunted by a family tragedy he helped bring on. In 1967, during a family game of touch football, he encouraged his older and only brother Mike to play defense, even though Mike was troubled by bad knees. Mike Menaker tore a ligament and died after surgery when he developed septicemia.

“Somewhere in my hideous id, I killed him,” Menaker wrote in his memoir. “I vanquished him from the field, and spoils are all mine.”

Menaker was an undergraduate at Swarthmore and received a master’s degree at Johns Hopkins University. He taught at private school and worked as an editorial assistant at the Prentice Hall publishing house before joining The New Yorker as a fact checker in 1969. He remained for more than 25 years, rising from fact checker to editor, handling work by Munro, Pauline Kael and George Saunders among others. He was also published in the magazine, starting with a story in which he imagines his brother returning from the dead, “Grief.”

In his memoir, he remembered being pushed out of the magazine in the mid-1990s by then-editor Tina Brown and handed off to her husband, Harry Evans, who was running Random House and made Menaker a senior editor. Over the next decade, his authors included Rushdie and such future prize winners as McCann and Elizabeth Strout. He also took on one of publishing’s more unusual assignments — the manuscript for the novel about Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential run “Primary Colors,” which he edited without knowing who wrote it. The 1996 bestseller was released anonymously, although the author was eventually revealed to be journalist Joe Klein.

“It reinforced the education I got at Swarthmore, which was very much explicative. You didn’t care who wrote a poem, you just read it,” Menaker told the Paris Review in 2014. “I’m not sure that ‘Primary Colors’ is a great work of art. I do know that it’s an awfully good novel, and it was a pleasure to have all the author complications cut away. So that was a sort of purist, graduate-school approach to something that was a commercial publication, but it was great fun.”

He was forced out from Random House in 2007 — his salary was too high, his profits too low, he would recall — and in recent years worked as a consultant for Barnes & Noble and on the faculty for the creative writing program at SUNY: Stony Brook University.

Contents

- Founders

- Political Positions

Chapo Trap House (sometimes known by the short name “Chapo”) is a for-profit political podcast founded in the spring of 2016 by three far-left socialists: Matt Christman, Felix Biederman and Will Menaker. Their twice-weekly show (which has since expanded to five contributors), named for infamous Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman and a euphemism for a home used to sell illegal drugs (a “trap house”), [1] includes coarse language and comedic parody.

As of January 2020 it reportedly grossed $152,000 per month through the website Patreon [2] and its weekly free performances were receiving an average of 150,000 to 200,000-plus downloads. Chapo characterizes its primary audience as “failsons”—economically adrift young, white, middle-class men, who buy into the anti-capitalist message because they “do not fit into the market as consumers or producers or as laborers.” Women reportedly comprise no more than 30 percent of listeners.[3][4][5][6]

In August 2018, the Chapo contributors published a book—the Chapo Guide to the Revolution—that debuted at sixth on the New York Times hardcover, non-fiction, best-seller list.[7]

Chapo commentary has been harshly critical of capitalism, work, economic growth, Republican politicians, and center-left Democrats (in particular Hillary Clinton) deemed insufficiently supportive of socialism.[8][9][10][11][12]

The podcast thrives on extremist statements. Menaker said that National Review founder William F. Buckley was not in “any meaningful way less racist than [neo-Nazi leader] Richard Spencer.”[13] In their book, the Chapo quintet wrote, “For all liberalism’s bragging about “getting things done, the only person who really got anything done during the Kennedy years was a young Marxist go-getter named Lee Harvey Oswald,” Kennedy’s suspected assassin.[14]

The Chapo founders met on Twitter after bonding over a shared political perspective. Biederman, who says he was terrible at and disinterested in formal education, was working as a freelance writer. Christman characterizes his work history before Chapo as “basically unemployable.” Menaker was working as an assistant editor for a publisher when Chapo was created, a job he left when the podcast became commercially successful.[15][16]

Background and Ideology

Chapo Trap House (Chapo) is a political podcast founded in spring 2016 by three hard-left socialists. Their twice-weekly show (with one free weekly episode and one weekly premium episode for paid subscribers) now features five contributors—the original founders, plus two more. In addition to political analysis from a hard-left, anti-capitalist perspective, the content includes coarse language and comedic parody. [17][18]

As of January 2020, Chapo’s weekly subscription-only premium content was reportedly grossing $152,000 per month from more than 34,000 subscribers on the website Patreon, and each of its weekly free performances were receiving 150,000 to 200,000-plus downloads. An October 2018 profile in the left-of-center Huffington Post described Chapo as “probably the most successful openly Marxist project in America since the 1970s.”[19][20][21]

The presenters claim to represent a “dirtbag left”: far-left supporters (such as the Chapo contributors) willing to offend “the sensibilities of ‘leftist’ language police whose only goal is sabotaging social solidarity in order to maintain their brands as arbiters of good taste and acceptable speech.” To play by leftist language police rules, according to the Chapo theory, is to become “handicapped by civility.”[22]

Chapo characterizes “failsons” as economically-adrift young, white, middle class males who “do not fit into the market as consumers or producers or as laborers” and have “just enough family context to not be crushed by poverty” who buy into Chapo’s anti-capitalist message. One Chapo co-founder portrays their generic “failson” listener as a 26-year-old male who “goes downstairs at Thanksgiving, briefly mumbles, ‘Hi,’ everyone asks him how community college is going, he mumbles something about a 2.0 average, goes back upstairs with a loaf of bread and some peanut butter, and gets back to gaming and masturbating.” Chapo contributors estimate women comprise no more than 20-30 percent of listeners.[23]

History

Chapo’s original creators were Matt Christman, Felix Biederman and Will Menaker, three friends who met on Twitter and bonded over a shared far-left political perspective. In early 2016, they were brought together on the podcast Street Fight Radio to criticize and mock the then-recently released film 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi. The success of this collaboration led to the first episode of what became Chapo Trap House in spring 2016.[24]

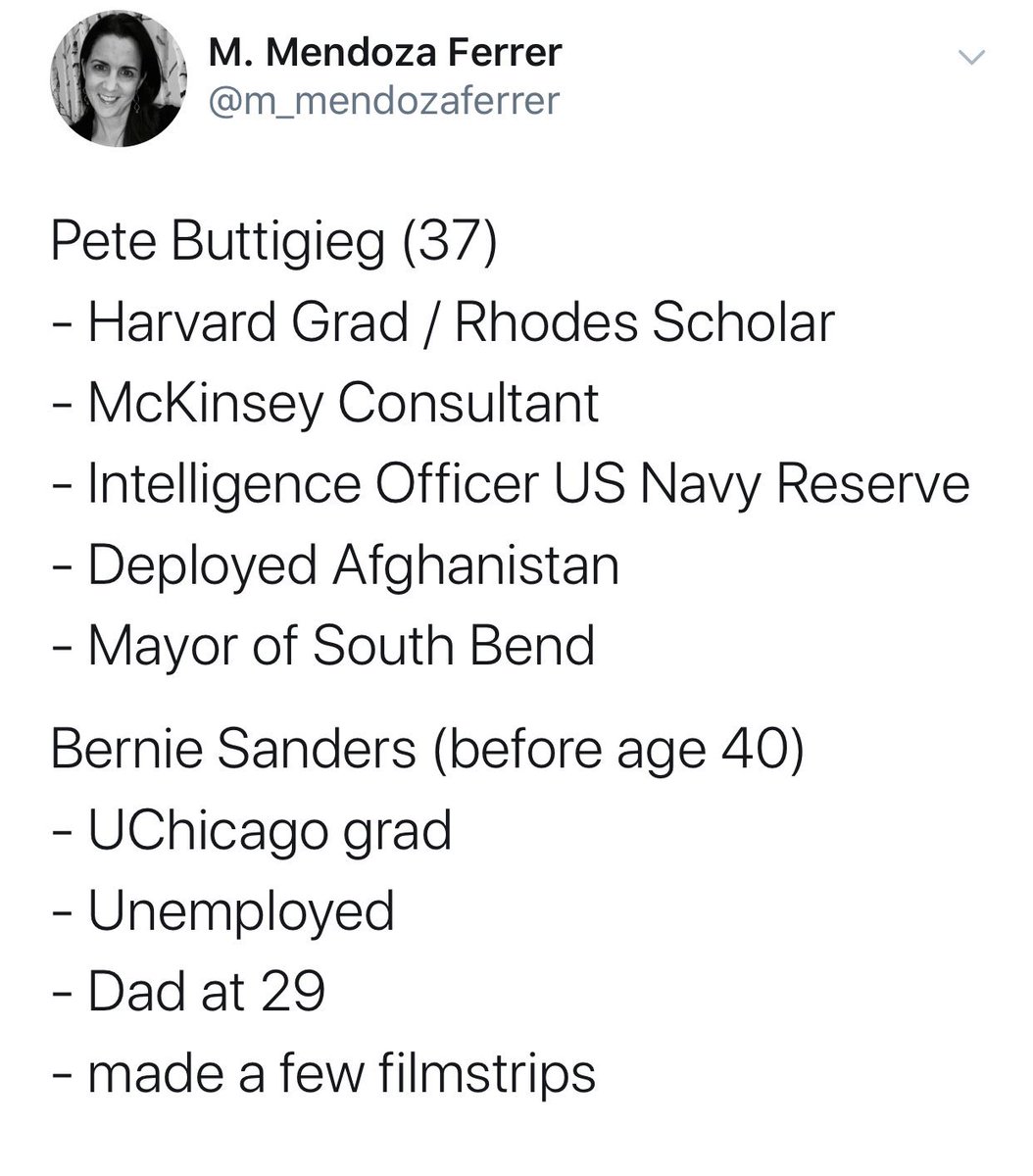

From the earliest episodes the trio heavily criticized both Republicans and Democrats, but their shows were animated and energized by their support for the presidential campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and the animosity of Chapo hosts toward both the mainstream center-left in general and 2016 Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in particular. As presidential prospects for Sanders faded through summer 2016, Chapo’s audience grew and became a refuge for Sanders supporters. By November 2016 subscriptions for the paid content had reached a reported $22,000 per month. The hosts had also begun to do live shows on tour, often playing to sold-out audiences.[25]

Their initial plans after the November 2016 election were reportedly to continue establishing Chapo as the leaders of the left-wing opposition to what was then widely expected to be a Hillary Clinton administration. Prior to President Trump’s election, they told an interviewer that a Trump administration would be both less enjoyable and less productive for their project.[26]

By August 2018 they had released a book entitled the Chapo Guide to the Revolution, written in the style of the podcasts authored by four of the five Chapo hosts. It continued in the podcast’s extremist principles, with one portion reading: “ten new laws that govern Chapo Year Zero (everyone gets a dog, billionaires are turned into Soylent, and logic is outlawed).” [27] It debuted at sixth on the New York Times hardcover, non-fiction, best-seller list. [28] By the end of 2018 the socialist podcasters were also selling t-shirts and other merchandise at the Chapo Trap House Store.[29]

Founders

Matt Christman

Chapo co-founder Matt Christman was born in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, attended Carroll Colleg, met his wife in Milwaukee and followed her to career stops in Ann Arbor, New York City, Spokane, and Cincinnati. He did not begin a career of his own prior to Chapo. “I had come to terms with the idea that I was basically unemployable and I was never going to have a job again,” he told an interviewer. “I was just going to be like a failguy.”[30]

Felix Biederman

Chapo co-founder Felix Biederman grew up in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, which he says he “hated,” calling it a “snobbish area” in a “city that is operated by criminals in the Democratic Party.” After graduating high school he worked in the gym at the nearby University of Chicago, and then attended and graduated from the University of St. Thomas (Minnesota). From there he came to New York City for a job in waste management that did not materialize. Prior to Chapo he worked as a freelance writer.[31][32]

“I didn’t know how to like, [expletive deleted] get internships or anything like that,” he told an interviewer in November 2016. “I was just like, bad at feigning interest or doing s**t I was supposed to do in school. I f****n’ hated school anyway. I was f****n’ bad at it. I’ve always been bad at that s**t.”[33]

Will Menaker

Chapo co-founder Will Menaker was working as an assistant editor at publisher W.W. Norton when the podcast began. He left his position a few months later when the podcast became commercially successful. He describes the home he grew up in as having conventionally center-left politics. His mother was an editor at the New York Times and his father an editor for The New Yorker. He graduated from Skidmore College and has said that he moved to the far-left as a result of the second Iraq War and the failure of Democrats to oppose it.[34]

Political Positions

Chapo and its hosts demonstrate doctrinaire hard-left socialism that is harshly critical of capitalism, economic growth, and work. Republicans and center-left Democrats are heavily criticized for either opposing Chapo’s socialist agenda or failing to sufficiently support it.[35][36][37]

Conservatives and Republicans

“Republicans have always been a racist party” and racism has always been a feature of the conservative movement, according to Menaker, who has said he doesn’t believe National Review founder William F. Buckley is in “any meaningful way less racist than [neo-Nazi leader] Richard Spencer.”[38]

The meaning of “freedom” for conservatives is the “freedom to exercise one’s God-given right to dominate anyone deemed lower than you,” they write in the Chapo Guide to the Revolution. “This includes rich over poor, men over women, employers over employees, white over black, and America over the rest of the world.”[39]

Democrats and Clintons

Menaker has accused both Bill Clinton (in 1992) and Hillary Clinton (in 2008) of running “fairly racist” presidential campaigns.[40]

In a critique of the center-left, Menaker has said: “I think the problem with liberalism is that it can only define itself in contrast to some other, or against itself. It’s always negotiating against itself to achieve some sort of consensus with capitalism and the right-wing, to buy us all a little bit more time.”[41]

“For all liberalism’s bragging about “getting things done,”” they write in Chapo Guide to the Revolution, “the only person who really got anything done during the Kennedy years was a young Marxist go-getter named Lee Harvey Oswald.”[42]

Also from the Chapo Guide: “Given the state of the pro-war, pro-Wall Street and pro-markets Democratic Party, which is as right wing as any political party should be allowed to be in the 21st century, the task of bringing socialism back has fallen to goofies like us.”[43]

On an Election Night 2016 Chapo live broadcast, after it was clear Hillary Clinton would lose the Electoral College, Biederman referenced her health episodes during the campaign, sarcastically telling the audience “if voters are too immature to vote for someone that collapses and vomits all the time, the joke’s on them.” Days later, in a Chapo parody, Biederman declared in faux-Clinton voice: “I may not be Dale Earnhardt… but I smashed into the [expletive deleted] wall because I couldn’t turn left!” (Dale Earnhardt, Sr., seven-time NASCAR champion, was killed in a crash on the final lap of the 2001 Daytona 500).[44]

Advocacy against Work

The Chapo Guide to the Revolution begins with an assertion that overthrowing capitalism and work itself is their desired objective: [45]

“Our case is simple: Capitalism, and the politics it spawns, is not working for anyone under thirty who is not a sociopath. It’s not supposed to. The actual lived experience of the free market feels distinctly un-free. We’ll tell you why and offer a vision of a new world – one in which a person can post in the morning, game in the afternoon, and podcast after dinner without ever becoming a poster, gamer, or podcaster.”

In an interview regarding the book, Christman and Menaker expanded on this thinking and their anti-work ideology.

“If you have ambition in your life to do something other than something you would get paid for,” said Menaker, “then I think you would be amenable to left-wing politics.”[46]

Atrios Twitter

“Because jobs suck and work sucks,” noted Christman. “…We have the [expletive deleted] lucre. We could make it so that people had to work less… Constant growth is just an insane system that no one questions.”[47]

Byyourlogic

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- “Top Patreon Creators.” graphtreon.com. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://graphtreon.com/top-patreon-creators^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- “Top Patreon Creators.” graphtreon.com. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://graphtreon.com/top-patreon-creators^

- Carter, Zach. “‘Chapo Trap House’ And The Slackers’ Revolt.” Huffington Post. October 13, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/chapo-trap-house-guide-to-revolution_us_5bb38cabe4b0d1ebe0e53c7b^

- “Chapo Trap House.” Soundcloud. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/chapo-trap-house^

- “Hardcover Nonfiction.” The New York Times. September 9, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/books/best-sellers/2018/09/09/hardcover-nonfiction/?mtrref=en.wikipedia.org&gwh=3C23DB7AB94E847DE0CD763FDD1AD28C&gwt=pay^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Scher, Bill. “Is This the Stupidest Book Ever Written About Socialism?” Politico. August 28, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/08/28/chapo-trap-house-book-review-219596^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Chapo Trap House. Chapo Guide to the Revolution: A manifesto against logic, facts and reason. New York: Touchstone , 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Chapo-Guide-Revolution-Manifesto-Against/dp/1501187287^

- Schafer, Joseph. “DOPE Interviews | Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker.” Dope Magazine. August 17, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/5/ and https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/4/^

- Schafer, Joseph. “DOPE Interviews | Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker.” Dope Magazine. August 17, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/5/ and https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/4/^

- Chapo Trap House. Chapo Guide to the Revolution: A manifesto against logic, facts and reason. New York: Touchstone, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Chapo-Guide-Revolution-Manifesto-Against/dp/1501187287^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Carter, Zach. “‘Chapo Trap House’ And The Slackers’ Revolt.” Huffington Post. October 13, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/chapo-trap-house-guide-to-revolution_us_5bb38cabe4b0d1ebe0e53c7b^

- “Top Patreon Creators.” graphtreon.com. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://graphtreon.com/top-patreon-creators^

- Carter, Zach. “‘Chapo Trap House’ And The Slackers’ Revolt.” Huffington Post. October 13, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/chapo-trap-house-guide-to-revolution_us_5bb38cabe4b0d1ebe0e53c7b^

- “Chapo Trap House.” Soundcloud. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/chapo-trap-house^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- “The Book.” Chapo Trap House. Accessed January 13, 2019. http://www.chapotraphouse.com/^

- “Hardcover Nonfiction.” The New York Times. September 9, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/books/best-sellers/2018/09/09/hardcover-nonfiction/?mtrref=en.wikipedia.org&gwh=3C23DB7AB94E847DE0CD763FDD1AD28C&gwt=pay^

- “Chapo Trap House Store.” Chapo Trap House. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://shop.chapotraphouse.com/^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Scher, Bill. “Is This the Stupidest Book Ever Written About Socialism?” Politico. August 28, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/08/28/chapo-trap-house-book-review-219596^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Schafer, Joseph. “DOPE Interviews | Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker.” Dope Magazine. August 17, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/5/ and https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/4/^

- Chapo Trap House. Chapo Guide to the Revolution: A manifesto against logic, facts and reason. New York: Touchstone , 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Chapo-Guide-Revolution-Manifesto-Against/dp/1501187287^

- Schafer, Joseph. “DOPE Interviews | Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker.” Dope Magazine. August 17, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/5/ and https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/4/^

- Schafer, Joseph. “DOPE Interviews | Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker.” Dope Magazine. August 17, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://dopemagazine.com/chapo-trap-house/2/^

- Chapo Trap House. Chapo Guide to the Revolution: A manifesto against logic, facts and reason. New York: Touchstone , 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Chapo-Guide-Revolution-Manifesto-Against/dp/1501187287^

- Uetricht, Micah. “The Horror and the Hopefulness of Chapo Trap House.” Jacobin. September 7, 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/09/chapo-trap-house-guide-to-revolution^

- Tolentino, Jia. “What Will Become of the Dirtbag Left?” The New Yorker. November 18, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/what-will-become-of-the-dirtbag-left^

- Chapo Trap House. Chapo Guide to the Revolution: A Manifesto Against Logic, Facts and Reason. New York: Touchstone , 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Chapo-Guide-Revolution-Manifesto-Against/dp/1501187287^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- Shade, Colette. “THE RADICAL CHEEK OF ‘CHAPO TRAP HOUSE.’” Pacific Standard. November 4, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://psmag.com/news/the-radical-cheek-of-chapo-trap-house^

- “Top Patreon Creators.” graphtreon.com. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://graphtreon.com/top-patreon-creators^

- “Chapo Trap House.” Soundcloud. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://soundcloud.com/chapo-trap-house^

Felix Biederman Twitter

See an error? Let us know!